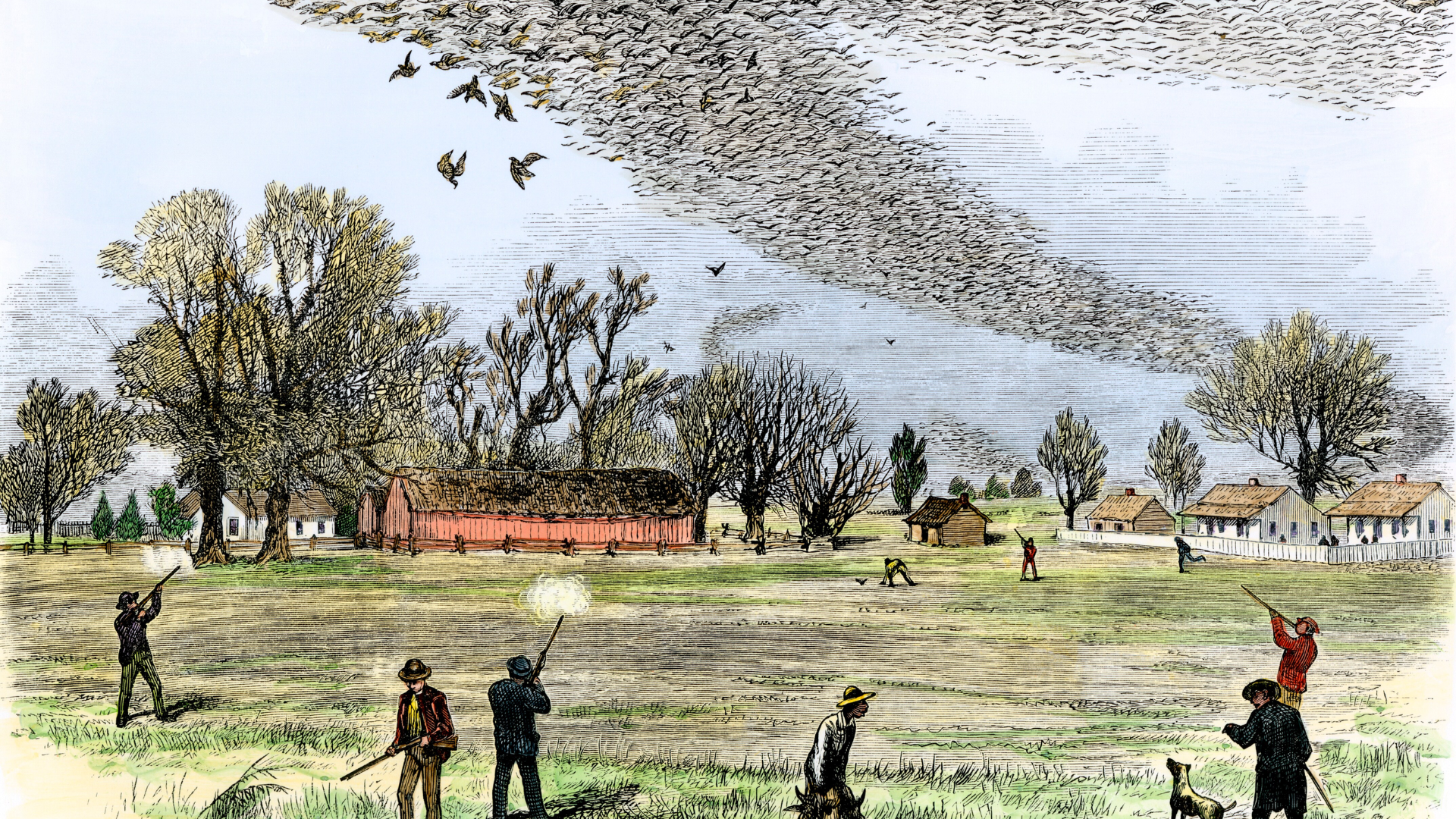

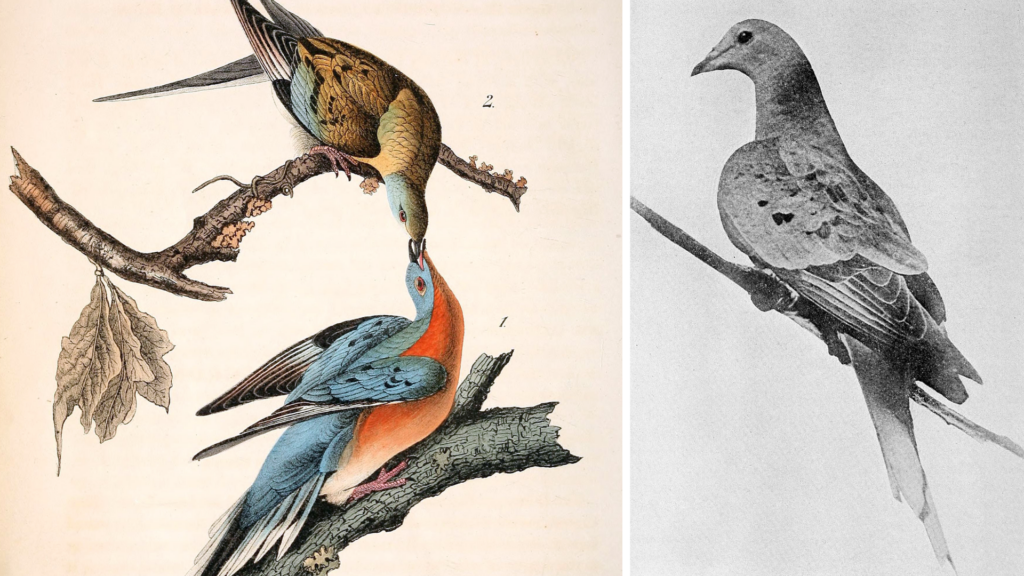

The disappearance of passenger pigeons from North American skies would have been unimaginable to people in the early 1800s. The beautiful, buff-gray and orange-colored birds were once the most abundant bird in North America, numbering from three to five billion. Flocks flying overhead could stretch for hundreds of miles and darken the sky for hours at a time.

Like many birds in Minnesota today, they nested near the Mississippi River where they found safe habitat in beech and oak trees. Intensive hunting and habitat loss led to their rapid decline and Minneapolis has the dubious distinction of being the location of the last recorded wild passenger pigeon nest and egg in North America in 1895.

The last wild bird was shot in 1907 near St. Vincent, Quebec. The last known surviving passenger pigeon, Martha, died alone in the Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914, four years after her two male companions died.

The Passenger Pigeons’ Important Legacy for Conservation

The speed at which the passenger pigeon disappeared—over just a few decades—made clear the potential for human-driven extinction on a massive scale, catalyzing early conservation efforts, including the creation of some of the first conservation groups in North America such as the National Audubon Society.

The loss of the passenger pigeon also spurred significant legal protections for wildlife for the first time. The Lacey Act of 1900, which made it illegal to transport illegally captured or prohibited animals across state lines, was one of the first federal laws enacted to protect wildlife.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, a landmark agreement between the U.S., Canada, and other countries, was directly influenced by the acknowledgment that unregulated hunting and habitat loss could drive species to extinction.

By the mid-20th century, scientists and conservationists began to affirm the importance of biodiversity and the protection of entire ecosystems to support threatened species. Environmental policies like the Endangered Species Act of 1973 were instituted.

Passenger pigeons had an outsized ecological impact while they were here. Because of their vast numbers and the long distances they’d travel they played a significant role in seed dispersal—especially oak and chestnut trees—influencing the composition of forests across North America.

In their absence they’ve also made a significant impact by rallying people to protect species and ecosystems.

Protecting Birds Today

Many bird species today are at risk of extinction due to habitat loss, climate change, and other environmental pressures.

While we can’t change what happened to the passenger pigeon, we can continue to honor Martha and her entire species by ensuring birds like the Henslow’s sparrow, golden-winged warbler, common loon, common tern and others have a safe home in Minnesota.

If we do our part today, 100 years from now people will still be able to see these birds flying overhead, nesting in trees and foraging along shoreline instead of learning about them only as a cautionary tale.

Let’s give birds a safe resting place in Minnesota…forever

Every $1 you give turns into $9 for land protection. A $50 gift becomes $450 in conservation power, enough to protect two acres of critical habitat for birds.

Learn more about the passenger pigeon:

- Passenger pigeon extinction was fast-tracked by Jim Williams, Minnesota Star Tribune.

- Why the Passenger Pigeon Went Extinct by Barry Yeoman, Audubon Magazine

This article was developed by the Minnesota Land Trust with research and copywriting assistance from OpenAI’s ChatGPT, an AI language model that helped generate and organize information related to passenger pigeons. All information has been reviewed and edited for accuracy and context.

Image Citations & Credits

Title: Passenger pigeon shoot, Author: Smith Bennett, Source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Public Domain, URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File.jpg

Title: The Passenger Pigeon (Audubon plate, crop), Artist: John James Audubon, Source: Wikimedia CommonsLicense: Public Domain, URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%27s_The_Passenger_Pigeon_(Audubon_plate,_crop).jpg

Title: Martha, the last passenger pigeon (1912), Photographer: Unknown, Source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Public Domain, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martha_%28passenger_pigeon%29#/media/File.jpg

Photo montage created by the Minnesota Land Trust. Images include Henslow’s sparrow © kgcphoto via canva.com; Golden-winged warbler © Carol Hamilson via canva.com; Common loon © jiristock via canva.com; Common tern © OKU via canva.com