Emerald ash borer (EAB) was first detected in northern Minnesota in 2015 in the Duluth area. The insect, originating from Southeast Asia, is an invasive pest that is expected to eventually destroy most of Minnesota’s nearly 1 billion ash trees, possibly impacting over a million acres of ash-dominated forest in Minnesota.

The proactive work of state agencies, partners and communities, and the cold winters in northern Minnesota, may have slowed the spread, but winters continue to warm due to climate change, and it’s only a matter of time before the remaining ash trees in the state are gone.

Besides their use in the urban and suburban landscape for reducing heat stress, cooling buildings, improving water and air quality, and reducing flooding risks, ash trees dominate many of Minnesota’s northern forests and hold cultural significance for Native American communities including the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Traditionally, Native American communities have had long-standing relationships with trees like the black ash (baapaagimaak) and accumulated Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) from hundreds—sometimes thousands—of years of direct contact with the trees and the local habitats in which they live. In northern Minnesota, ash trees are important for maintaining water table levels and mitigating surface water runoff to support manoomin (wild rice) in the St. Louis River Estuary.

Minnesota has more than 1 million acres of ash-dominated forest (2019), more than any other state.

A 20-year old ash tree sequesters up to 41 pounds of carbon annually. Minnesota’s ash forests store around 187 million tons of CO2, mostly in forest soil.

Warmer winters due to climate change can result in an increase in pests and insects.

Across the state, winters are warming fastest in northern Minnesota, with an average increase of 7.1° F since the 1800s and only 5.2° in the rest of the state.

The Impact of Losing Ash Trees in Minnesota

Losing 1 billion ash trees, the majority of which are concentrated in northern Minnesota forests, could result in converting one million acres of forest to non-forest ecosystems.

The detrimental impacts of this shift include less carbon sequestration capacity and changes to the landscape that would negatively impact the existing resident wildlife as well as migrating birds, like the rusty blackbird, who rely on the forested wetland habitat in the St. Louis River Estuary as a stopover point.

While the eventual loss of most of the ash trees in Minnesota is all but certain, there is hope—and a strategy—to preserve forest habitats through planting diverse, climate change-resilient native tree species now.

Strategic Partnerships Preserve Critical Wetland Forests

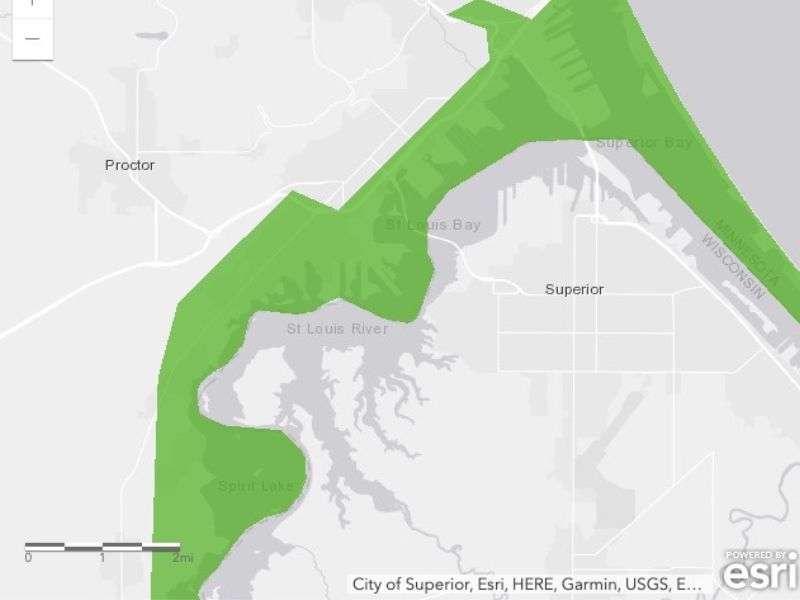

Led by the Minnesota Land Trust, in partnership with the City of Duluth and the Community Action Duluth Stream Corps (DSC), planting of 25,700 trees and shrubs is now underway as part of the Coastal Wetland Forest Restoration for Birds Initiative.

The planting takes place across 32 acres which will improve the ecological integrity of 175 acres within the St. Louis River Estuary Important Bird Area, positively impacting 52 different species of migrating birds that are designated Species in Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), including the rusty blackbird, yellow warbler, and magnolia warbler.

The Duluth Stream Corps began the first round of planting in May 2022 at Chambers Grove, Rask Bay, and North Bay, all situated within the St. Louis River Estuary Important Bird Area.

The goal of the project is to mitigate the threat of EAB within this high-quality coastal habitat by planting trees that will survive even after black ash trees die off in the coming years, preserving the coastal forests for migrating birds and resident wildlife, and to help maintain the conditions necessary for manoomin to thrive.

The project will also improve species biodiversity, increasing the resiliency of Minnesota’s coastal forests in the face of climate change.

Climate Change Adaptable Northern Forests

The new trees being planted include a diverse mix of native tree species that grow in the area but are better suited to the warmer and drier conditions that are increasingly common in northern Minnesota.

These trees, including red maple, silver maple, and bur oak, can be found in the warmer regions of southern, eastern, and western Minnesota.

Northern hackberry trees will also be included as a possible replacement species for Indigenous cultural uses as suggested by Natural Resources staff at Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Tree planting will span two seasons and once completed, the City of Duluth will assume long term monitoring and maintenance through their Duluth Natural Areas program. Across the border in Wisconsin, the Lake Superior Reserve is conducting a partner project on river islands in the immediate vicinity with the same intent, increasing the positive impact to forested wetlands and migrating birds in the region.

According to Gini Breidenbach, St. Louis River Restoration Program Manager, “Important research is ongoing about how best to support the ecology of ash forests once the ash trees die off. But because EAB is here now threatening these important coastal wetland habitats, we feel strongly that action, based on the best available information we have, is also necessary. This project takes an adaptive management approach to support these forests and the birds that use them.”

Help Build More Resilient Forests in Minnesota

Rusty blackbird populations have declined 85–95% over the last 50 years, and according to recent research by the University of Minnesota Duluth Natural Resources Research Institute (NRRI), the St. Louis River Estuary may have a disproportionately large impact on the wellbeing of this swamp- and water-loving bird species.

Data shows that rusty blackbirds use the region as a stopover site longer than typical migrating birds, with 23% staying 18–24 days. The region provides vital habitat when they’re most vulnerable, during fall migration as they’re making their way from breeding grounds in Alaska and Canada down to the Midwest and southeastern United States.

The preferred locations for rusty blackbirds in the estuary include Rask Bay and North Bay, locations that are part of the Coastal Wetland Forest Restoration for Birds project.

Article Contributors

Website Publication Date: September 30, 2022

Originally published in the Minnesota Land Trust 2022 Fall Review.

Written by: Sarah Sullivan, Communications & Marketing Manager

Professional review by: Gini Breidenbach, St. Louis River Restoration Program Manager

More Minnesota Land Trust Restoration Projects

- Restoration Improves Forest Health, Mitigates Wildfire Risk in Northern MinnesotaThe buzz of chainsaws is punctuated by a crack of wood. Though it may seem counterintuitive, even jarring, this is the sound of forest restoration—specifically, restoration of 115 acres in Lake County, Minnesota. The owners of the property, situated directly between Split Rock Lighthouse and Gooseberry Falls State Parks, acquired a conservation easement in 2019,… Read more: Restoration Improves Forest Health, Mitigates Wildfire Risk in Northern Minnesota

- A Century Old Farm’s Greatest Yield YetThe property in the Minnesota Land Trust’s Rum and St. Croix River Conservation Priority area includes the forested northern shore of Rock Lake and is situated between a Walmart Supercenter, golf course, and two residential developments near the growing community of Pine City, Minnesota. The most obvious and, likely lucrative, opportunity for retired farmer… Read more: A Century Old Farm’s Greatest Yield Yet

- Restoring Coastal Wetlands for Migrating BirdsEmerald ash borer (EAB) was first detected in northern Minnesota in 2015 in the Duluth area. The insect, originating from Southeast Asia, is an invasive pest that is expected to eventually destroy most of Minnesota’s nearly 1 billion ash trees, possibly impacting over a million acres of ash-dominated forest in Minnesota. The proactive work of… Read more: Restoring Coastal Wetlands for Migrating Birds

Funding for the Coastal Wetland Forest Restoration for Birds project was secured through a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and is also supported by Minnesota’s Outdoor Heritage Fund as appropriated by the Minnesota State Legislature and recommended by the Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council (LSOHC).