Candace and Steve Gouze

It’s prophetic, in a way, that Candace Gouze’s birthday falls on Earth Day. After all, she’s led her family’s extraordinary efforts to protect their own little piece of the earth on Washburn Lake in Cass County.

Over time, little by little, bit by bit they’ve acquired property around their family cabin — wetlands where loons nest, a patch of peaceful woods, neighboring waterfront lots, land along a creek that flows between Washburn and Lake George. Today it adds up to three miles of shoreline and 236 acres of forest that are all protected forever through a conservation easement with the Minnesota Land Trust.

“My mom has always been a conservation-minded person,” said Candace’s daughter, Katie Bliss. As a little girl, Katie was never allowed to buy anything packaged in plastic and even her sandwich had to be wrapped in wax paper, she said. That tradition of conservation has now permeated the whole family, especially when it comes to protecting Washburn Lake.

“This project was a dream for both of us.” – Steve Gouze

Whitefish Lake

Beginning in the early 1990s, they focused on buying contiguous tracts of sensitive land that had a clear impact on the lake’s ecosystem. What drove them was the promise of protecting nesting sites for loons and the subtle beauty of the northern forest.

A perfect fit for their goals and their family, the Gouzes decided to put their accumulated property into a conservation easement with the Minnesota Land Trust. “My mom was very excited about the prospect of protecting it in perpetuity,” said Katie. “Creating the legacy was very important to them. They want this work to be bigger than this generation.”

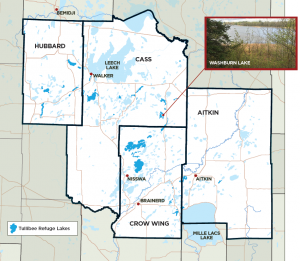

Now, they are part of a much larger legacy project to protect one of Minnesota’s greatest treasures: our cold-water lakes.

The Minnesota Land Trust and its partner, the Northern Waters Land Trust, are working to protect lakes in Minnesota that, like Washburn, are cold and deep enough to act as a refuge for a sentinel species of fish — tullibee. Also known as herring and cisco, the silver fish are a rich food source for predators like walleye and a key link in the food chain for aquatic species.

“They call it the canary in the coal mine,” said Kathy Moore, executive director of Northern Waters Land Trust. “Once tullibee start being impacted, it impacts the entire food chain in a big way.”

In the last three decades tullibee have declined by about 60 percent in lakes across the state. One reason is climate change. Tullibee can’t survive in water with surface temperatures above 76 degrees Fahrenheit. The other threat is development — lawns, pavement, and agriculture — which drive nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen into lakes, creating a rich environment for algae and other aquatic plants that pull oxygen out of the water.

In shallow lakes, tullibee don’t have a chance. But in deep water lakes they can survive by going to the cold depths as temperatures rise in the summer.

Minnesota state scientists proved it¹ after a drought in 2006 resulted in fish kills all over the state. They found that in clean, clear, deep water lakes where oxygen levels remained high at lower depths, the tullibee survived.

Scientists from the Minnesota DNR and the University of Minnesota identified hundreds of lakes in the state — far more than anywhere else in the country — that would be able to support tullibee decades from now when the average temperatures will be much higher. That makes it imperative to preserve Minnesota’s coldest lakes and the fish that depend on it them.

But which ones should we protect?

photo by Rebecca Field

Researchers found that phosphorus levels in lakes increase significantly when the watershed that surrounds it is more than 25 percent developed or depleted of natural land cover, especially forest. Phosphorus comes from farm fields and flush into the waterways across impervious surfaces like streets and parking lots every time it rains.

That doesn’t happen when the land surrounding a lake is at least 75 percent forest. Today, the two land trusts are working together to target potential conservation land around 50 deep lakes in the Upper Mississippi Watershed that are surrounded by forest, but which are threatened by development. Progress is slow but steady.

To advance this important effort, the Minnesota Land Trust is in part relying on funding provided by the Outdoor Heritage Fund as recommended by Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council. “The tullibee lakes partnership is now in the fifth phase of state funding for the project. A new proposal, which if approved by the Legislature in the 2019 session, would add thousands more acres and feet of protected shoreline,” said Ruurd Schoolderman, Minnesota Land Trust program manager for the region.

This project will result in a true “legacy” of keeping our northern forests wild and our cold-water fisheries world class. And it provides a great model for using a scientific, targeted approach to conservation while simultaneously helping individual lakeshore property owners achieve their own goals of long-term protection for the places that they love.

For people like Steve and Candace Gouze, their grandchildren will be the next generation in their family to spend summers catching walleyes and watching baby loons grow up in the protected bays and wetlands near their cabin. “I don’t know what it’s going to be like for them when they are adults,” Candace said of her grandkids. “But this is one way that we can try to make sure that we will all be better off.”

¹ Craig P. Paukert, Bob A. Glazer, Gretchen J. A. Hansen, Brian J. Irwin, Peter C. Jacobson, Jeffrey L. Kershner, Brian J. Shuter, James E. Whitney & Abigail J. Lynch (2016) Adapting Inland Fisheries Management to a Changing Climate, Fisheries, 41:7, 374-384, DOI: 10.1080/03632415.2016.1185009

Support for this effort has in part relied on funding provided by the Outdoor Heritage Fund, as appropriated by the Minnesota State Legislature and recommended by the Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council (LSOHC).

Support for this effort has in part relied on funding provided by the Outdoor Heritage Fund, as appropriated by the Minnesota State Legislature and recommended by the Lessard-Sams Outdoor Heritage Council (LSOHC).